There have now been countless comparisons of the corona pandemic and the climate crisis. Many highlight how our Earth is apparently healing or how similar the crises are (they aren’t). Many that the climate crisis needs to find the PR agent that Covid-19 has (quite possibly!). I understand these posts. Optimism in the face of pure dread is a reasonable coping response. The memes too are an excellent giggle – a release from the madness – and represent some of the sheer frustration of these currently competing emergencies. I lean toward dark humor (and it’s been dark out there friends when we laugh about the decline of our own species to benefit nature). Humor is a coping strategy; it’s come out in force and I appreciate humans more because of it.

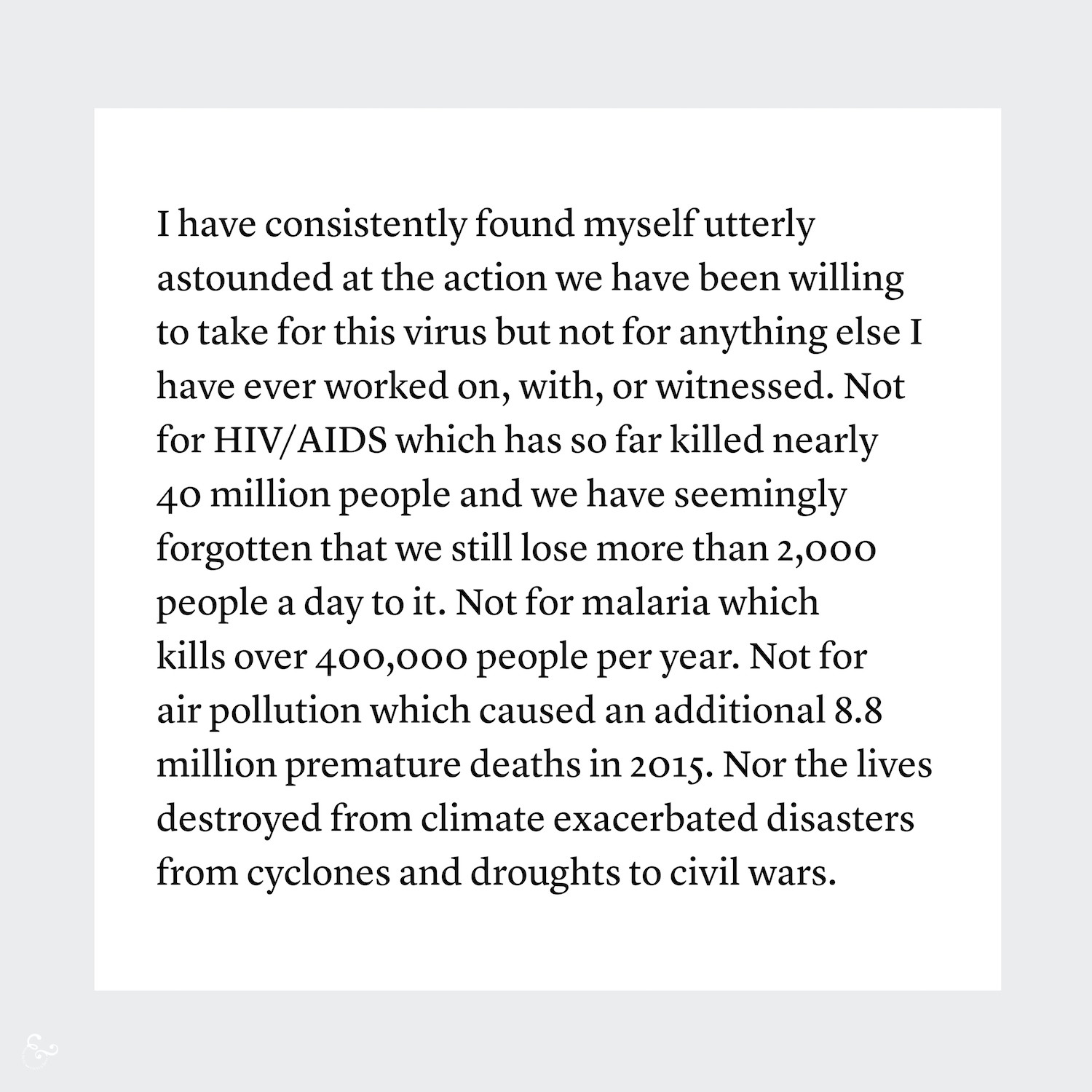

I understand the frustrations deeply too. I have consistently found myself utterly astounded at the action we have been willing to take for this virus but not for anything else I have ever worked on, with, or witnessed. Not for HIV/AIDS which has so far killed nearly 40 millionpeople and we have seemingly forgotten that we still lose more than 2,000 people a day to it. When I started making t-shirts for it 6,000 people per day were dying. Not for malariawhich kills over 400,000 people per year. Not for the 5 million children who die worldwide from hunger. Not for when I felt like I was silently screaming into the void last year in Cambodia when people began to starve during the horrific climate-induced drought and I saw the first climate refugees pile up into trucks under moonlight. Not when children started having fits from dehydration from the lack of water and we closed all the schools and businesses. Apparently I trained for a mandated lockdown by practicing a naturally enforced one.

I’m still shocked we don’t act on the pollution deaths of at least five million humans that we have decided are an absolutely acceptable consequence of hypercapitalism and poverty. A recent studyhighlighted that air pollution caused an additional 8.8 million premature deaths in 2015. Nor the hundreds of thousands that are dead, or the millions of lives destroyed, from climate exacerbated disasters from cyclones and droughts to civil wars. Not even for the 1 billion cases of influenza which kill about 290,000 – 650 000 each year. Physical distancing and these extreme lockdown measures would (and perhaps will this year) solve a lot of flu deaths. We also certainly don’t consider standing still for the thousands of species we are sending into extinction from butterflies to orangutans to the koala. They’re merely collateral damage in our quest to consume evermore. There is never a campaign to close down the world for any of this.

I understand the deep pain that comes from watching this. From knowing we have to act – with the understanding this is the right thing to do – but wondering why we don’t sufficiently on nearly everything else. Why has this been the thing we will shut the global economy for? Why have we not come together on anything else like this? The biggest crisis facing our civilization is climate change and other than the last recession we’ve only managed to make it worse each year. We have done nothing of this scale whatsoever to stop runaway heating, land-use change and biodiversity loss. We have not even seriously thought about moving away from the growth-on-growth model we seemed cemented to. Why this? Is it because the majority of our politicians fall into the group that are most vulnerable? They are on average over 60, wealthy and male. Or are younger but with other underlying health issues? Is it that the climate crisis will disproportionately affect young people and those in vulnerable communities, but the pandemic specifically impacts the older and is indiscriminate of wealth (better access to healthcare aside)? Or is it that conservative voting groups propping up many of those in power, are made up of older people and more men? All of those other crises don’t affect this group anywhere near as much for the remainder of their lives – is that the answer?

I hope not but it’s hard not to be a cynic when you lay it out like that.

“Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable.” – Milton Friedman

The issue with data

One of the difficult things with Covid-19 has been actually understanding accurate data. We have some great, if not at times conflicting, pieces from reputable sources but they’re only doing the best they can with what they have. In nearly every country we don’t have large scale testing so we really don’t know how many people are infected. The studymost of us know is the headlines made by Imperial College London which concluded that if we did not aggressively contain the virus, the UK would be staring down the barrel of half a million deaths and the US more than two million.

That is now juxtaposed against a study published by the University of Oxford suggesting that halfof the British population may already be infected and the death rate is very low at potentially 0.1%. This number comes because the only thing we do understand is deaths. A research team recently concluded that the true fatality rate in China was around 0.5% due to the large number of asymptomatic cases. If we use different fatality rates in our models (which currently range from less than 1% in Germany and Iceland to 10.8% in Italy at time of writing), you can end up at the number of infected people possible in the population.

But deaths themselves aren’t accurate either. A (probably) statistically significant number in the deaths would have likely died anyway or perhaps from a simple case of influenza as they were approaching end of life (i.e it didn’t matter what was on the horizon, they wouldn’t have survived it). Or they may have died from another reason but had also been infected with Covid-19 and included in the tally. There may also be more deaths than we know. Anyone who has spent time in rural low-income countries knows that deaths are often not accurately determined and recorded, or are misattributed. We are still currently dealing with a globally relatively low number of deaths at this stage (it has hit 30k at time of writing / 80k at time of publishing) so small numbers can still materially affect this.

What we do know clearly is that young people are extremely unlikely to die from this compared to those over 70. We also know that we have heavily skewed our testing to the more ill amongst us, likely artificially inflating the death rates.

Data is also constantly used by the media without qualifiers and context. This too is understandable. Huge numbers in the form of a ticking death rate are easy to present and cause the kind of anxiety and drama that is addicting. Can you imagine if we had a daily ticker of HIV/AIDS deaths or those related to air pollution?Or what about a ticker for something that we’re nearly all exposed to in the global food industry, and have individual control over where it is accessible to us; the rate of deaths relating to obesity? At least 2.8 million people die each year as a result of being overweight or obese with WHO stating it has reached epidemic proportions. Pop that on the front page of every news stream each and every minute of the day and we can induce the same frenzied craze and anxiety.

Finally, is it even the virus that’s the problem? We can see that it largely affects the elderly and people with multiple other health conditions. According to a studyin Italy, so far more than 99% of the fatalitieswere people who suffered from existing medical conditions. More than 75% had high blood pressure, about 35% had diabetes and a third suffered from heart disease. The average age of those who have died in Italy is 79.5. Was it the virus that killed them then or poor health? The virus is now spreading throughout the United States where 40,000 people a month alone die from obesityrelated causes. Combine that with all the other health issues in the country – individual and systemic – and it’s no wonder you see deaths in the hundreds of thousands being predicted.

In the climate crisis we have good, solid data. The data has often been conservative – we have already reached past the extremes on some predictions – but we have good data. We don’t have everything due to feedback loops and the unknown but all that is likely to make it worse, not better. If we have been able to act on a crisis with this much conflicting data and so much that will not be known until it is over, we can act on what we absolutely do know, and can confidently predict, in the climate crisis.

We invade tropical forests and other wild landscapes, which harbor so many species of animals and plants—and within those creatures, so many unknown viruses. We cut the trees; we kill the animals or cage them and send them to markets. We disrupt ecosystems, and we shake viruses loose from their natural hosts. When that happens, they need a new host. Often, we are it. – David Quammen, Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Pandemic

The issue with risk

Along with seeking to really get to know the data – much of which we likely won’t until the peak has long passed – we don’t understand risk that well as humans. We think we do but we many of us erratically act on risks in our personal lives and have risk profiles all over the shop (understandably). Systemically we have the same issue too.

We knew for example that a pandemic was likely. All the experts advised governments on it. In 2017 UK Government risk assessmentit outlined that pandemic influenza was ranked as one of the most likely options with the highest detrimental impact on society. It’s one of many of course. I’m not his biggest fan at all, but Bill Gates pointed outin 2015 that we were completely unprepared for a coming pandemic (insert joke on fighting viruses since the creation of Windows). He wroteabout it a decade ago too after we saw H1N1 grab a lot of attention. The WHO ironically released a reportlate last year about our growing risks of pandemic and lack of preparedness. Singapore has had a pandemic preparedness response plan since 2010. That same year the World Economic Forum Global Risks report outlined pandemics and infectious diseases again citing an increased likelihood in loss of life and loss of productivity and economic loss. They’ve been on there for years. And personally in 2018 I listened to one of my favorite podcastsexplain why a pandemic was a real possibility.

I lived in rural Cambodia when we had an epidemic of hand, foot and mouth disease killing young children when they entered hospital and were treated with steroids. The WHO ended up there and we lived a very small scale of the steps we are now witnessing globally as the issue was traced and discovered. I remember having to be part of education sessions explaining certain rumored solutions weren’t going to solve the issue; theories that spiked sales and seemingly came from nowhere. A few years ago I was running a workshop in Central America when Zika broke out. Wind back many years earlier and I was in a plane on the way to Tokyo with nearly every passenger wearing a face mask due to the latest SARS outbreak. I’ve seen these events first hand and the risk has barely registered.

We have a problem with pricing-in this risk. We know for example that a lot of our risks come from eating animals whether it’s a wild market in China or factory farmed meat across the world. In this particular pandemic it seems to have perhaps transferred from bats to pangolins(the most trafficked animal in the world) which people, mostly in Asia, eat.That shouldn’t incite any racist vitriol.It’s absolutely just as bizarre, or normal, to eat a lobster. Just as odd to raise billions of cows to slaughter them in a factory. Just as weird to milk them whilst they are covered in their own feces. Just as horrific to breed minks to make fashion fur jackets. It’s far more incomprehensible to shoot stunning wild animals as a sport. Or force feed geese until their livers nearly explode for foie gras. Or shoot up dolphins and whales for fun and to eat soup and burgers. Us humans do strange things (or completely normal if you see it that way) no matter which country we’re in. To me it’s actually quite a wonder we don’t contract more diseases from these practices; a small little miracle in a world that has exploded in population by doubling in the past fifty years to over seven billion. That population growth has seen us move into more and more habitat of wildlife increasing our risk of zoonotic diseaseseven further. These are only facts. They are often interpreted emotionally but they needn’t be.

We know that eating animals in this way – whether from the industrialized agriculture system we’ve created that has completely ruined lands and lives (stood aside from ethical questions) or from wet markets – carries with it a chance of systemic collapse. Of a global pandemic. Of pushing an ecosystem so far it breaks. We believe it’s on the rise. That risk is may be small (or big in the case of the impact of agriculture on climate change), but the consequence it causes – as we are now living through – is unbelievably huge. Knowing this, we should be costing it in. A dollar soup or cheap mince packet doesn’t account for this risk in any way. That of course brings with it numerous other issues in addressing poverty and inequity, but in economic terms only we can understand this.

Such acute pandemic is unavoidable, the result of the structure of the modern world; and its economic consequences would be compounded because of the increased connectivity and overoptimization. – Nassim Nicholas Taleb

We have the same problem with climate change of course. The chance of climate change literally breaking our world as we know it is increasingly more likely. But more-so, the impact of it if it did happen is unfathomably large. It already happens. It’s going to occur much, much more. We should be pricing that in (something the weak cost of carbon barely attempts to do). Even climate change itself is exposing us to the risk of more pandemics. Our human influence is expanding the habitat of mosquitoes into new areas, putting more and more people at risk. Simultaneously, thawing of the permafrost can lead to the exposure of bacteria that has been dormant and buried in the ground for hundreds of thousands of years.

A note on wet / wild markets

I have spent a lot of time living in Cambodia and in our region this is one of the primary ways in which people eat. It is largely more sustainable than intensive agriculture. Is it hygienic? No. But banning markets is not a simple solution and it comes from a place of enormous privilege. There’s no bi-partisan call to be banning factory farming from the same large group admonishing wet markets. We need to also address the underlying economic, social and cultural issues of why we sell wildlife like this. We still do not have electricity in most of the villages we work in. Even when we do it’s hydropower so when droughts happen, as it did again all last year, we barely had any power. After a while everything shut down. We certainly don’t have refrigerators. These markets are an essential source for staying alive. When we understand and work with this, alongside resolving hunger and poverty, strong regulations would likely be more helpful than a wide ranging ban (which tends to create black markets that are even harder to monitor).

The price of life

The risks we do and don’t take often lead to discussions alluding to the price of life. And during this pandemic, that it is worth it all to save lives. That there is no price of life too high. Except of course that we put a price on life every single day. We might save thousands of mostly elderly people or those who fall ill with co-morbidities, but we’re also doing that at the cost of other lives. We know women will suffer more domestic violence; this has already begun in earnest. We know people will likely suicide more; the calls to crisis lines have already exploded. How many more deaths of despair will we see over the coming years all stemming from the period everything fell apart? We know gambling and alcohol use is going to increase. We know children will be placed in horrific situations with no outlet or option to leave. We know this will cause them trauma and in economic terms affect their productivity for the rest of life. We know if we close schools for extended periods we’re going to affect a great number in this generation. We know many charities are going to have donations severely pulled back and that will cause the deaths of many others cascading into years as money around the world dries up.

It goes on. We know that the impacts from this is going to impoverish many families, often those already more vulnerable, who will never recover. We know people experiencing poverty die earlier. We know that all of these issues will most affect people with many more years of quality life left than the elderly we are saving by taking all these measures. Are we going to count up how many quality years we saved vs how many we lost? And how willing are we to extend this control and significant reduction in quality of life to save say 250,000 lives? What’s the threshold here where we have determined what is and isn’t worth it? What loss of culture, art and human contact are we willing to give up, potentially leaving a gaping hole for the rest of our lives? We can go much deeper and darker of course. As our governments assert all control over our freedom and enforce police and surveillance states, how long are we willing to live like that? What happens if temporary measures become permanent? Are we happy to give it all up?

With the steps taken in this pandemic so far, we have decided the cost of the lives we are now – and will be – causing the death of, are outweighed by others dying from the virus right now. Within our current system, economically doing something is concretely better than doing nothing; that has been modelled and seems entirely clear. Morally is another matter and depends on your values and scientific rigor. Who gets to choose which lives are worth it?

If the pandemic continues to spread and ends up rampaging the African continent, lower-income countries might potentially face a disastrous choice. I’ve lived in a number of these places for years; no safety net will catch anyone and the decision will be to lose your elderly or lose your children in the ensuing hunger and years of new setbacks. Do you choose your grandparents or your child? Philosophically, the former would be the choice – children have far more years of quality life to live. It remains a horrendous choice. If the disaster went on long enough in industrialized countries that would eventually present itself too. On top of that, many of these countries can ill afford to lose their doctors. There are already not enough (and you can trace that problem back to colonialism). A pandemic of scale would wipe too many out; and the resulting loss of life from those who can no longer be appropriately attended to. One of the wealthiest countries in the world, America, is absolutely straining under there lack of response already. What happens in a country that the world has wreaked havoc on for years that doesn’t have the underlying finances?

Not doing anything has a huge moral and economic cost. Doing everything does too.

The Earth is healing (another data issue)

Which is why the posts being shared of the Earth recovering are hard to swallow. Some of this is absolutely factual in the sense that air pollution has dramatically lowered in a number of areas. China saw its emissions shrink by a whopping quartercompared to the same period last year. In Delhi, where the air pollution index has even dropped into the “good” range, you can see the Himalayas for the first time; a genuinely heart burstingview. Knowing wild animals are getting a reprieve is delightful. With industries grinding to a halt and with daily traffic nearly completing stopping, it’s lifting the smog so many of us live under. Not entirely of course; mining and construction continues on. But it is evident. There are less of us destroying the earth on a daily basis. Though many are still shopping up a storm from home, the less money there is, the more this decreases too. This isn’t coming from the virus; it’s happening due to a reduction in demand.

It’s also probably not permanent. In fact, we’re more likely to see a backlash. If the 2008 recession is anything to go from, we’ll pollute more in the decade after as if we didn’t learn a single lesson (we didn’t). A lot of people expect a sharp spike if things go “back to normal”. We don’t know of course; maybe the world will change forever. Maybe we will finally change our normal. I – perhaps for the first time – hold some hope that we may.

Many of us will realize we can work from home and work more flexibly whilst consuming less. Many small businesses are changing how they work. I’m less convinced by big players of industry though. Many are asking for and receiving bailouts without being tied anywhere near well enough to greener outcomes. They are not being mandated to switch to renewable energy, find solutions to issues such as industrial heating and creating innovative business models that will see them emerge very differently than they existed so unsustainably before. We also do not need to bail out every single business. We can let some fail that aren’t critical to life and aren’t able to operate in a way that’s compatible with our planetary boundariesin any form.

If we’re going to compare the climate crisis with the corona pandemic, who is doing the calculations? The deaths saved by the reduction in air pollution may well outweigh the deaths by the virus; in China with only 3,000 or so virus deaths this will likely be the case. A Stanford University professor and environmental resource economist estimated that China has probably saved over 70,000 livesfrom the reduction of air pollution (it normally loses about one million people per year). We could have reduced air pollution without requiring a pandemic if we had made a serious attempt at reducing the progress of climate change. The consumerism stopped in its tracks would have an exceptionally positive impact on the environment once that stops supply particularly in land-use change and shipping emissions. Will the benefits of that outweigh the enormous waste in stockpiling, the insanely high plastic usage we’re seeing and refusal of businesses to accept reusables, the uncountable single-use face masks and gowns that will be landfilled, and the food waste middle to high income families will now create more than ever before?

We don’t know of course. There will be so many calculations to be made like this. Importantly, this isn’t how we would have enacted changes to the climate crisis. No-one worth their position was calling for a sudden halt to numerous industries with absolutely no safety net in place. In fact, many of us – whether as experts or public advocates – have been calling for a just transition. Most people who want to see action taken and have empathy do. Spain and Germany have both provided leading examples of how to justly transition workers in coal and it’s been inspiring to watch unfold.

That’s how we would want change to be made. We would have wanted it over decades too to spread it all out but we chose not to act at all which means it needed to be done swiftly but kindly and equitably. A pandemic that destroys the lives of so many millions, that removes such a large scale of jobs overnight, that completely dries up everything in sight outside the healthcare industry, is not what we would ever have wanted for the climate change movement. We never wanted to see 3 million Americans claim unemployment in one day; the largest in history. We never wanted to see the same happen in Australia which avoided the worst of the last recession by somewhat horrifyingly handing people cash to buy more things. We wanted plans, careful timelines, safe guards, inspiration and measures for the poorest and most vulnerable amongst us. We wanted the wealthiest in our cohort to hoard a little less.

None of this great pause on nature is that important for long term impact. It’s not evenly distributed either. Industrialized countries and BRIC might be seeing more benefits because we’ve messed up the most. Anyone that’s been to the Serengeti or Rwandan gorillas will know that these places might suffer. It is the expensive (necessarily so) ecotourism that provides the money for rangers and conservation staff (it shouldn’t be of course but it’s the world we live in). If major private donations aren’t provided, who will protect the animals from the poachers? How will we keep our conservation efforts going? In Indigenous managed lands, how will land be protected if people contract the virus? In an effort to stay as far away as possible from those who might spread it, tribes need to retreatfurther away (and away from missionaries), offering up an opportunity for illegal mining and logging.

What is of the utmost concern is what we do from here. That, and pretty much only that at this point, will shape where we have decided to go as a world and the environmental impact we’re going to have,

What is normal anyway?

Apparently we need to go back to normal from here (although many are starting to disagree including even the Financial Times). But normal wasn’t sustainable. We have been ratcheting up more environmental disasters than ever before. They’re more frequent and more intense. In the last couple of years alone vast swathes of the entire world have been on fire in an unusual way. We have seen multiple reef bleaching events. Millions of us have choked to death on pollution. Desertification is taking hold everywhere. There are billions fewer wild animals now than there were a mere fifty years ago. We thought it was fine to have hundreds of millions of people living in poverty and food insecurity. We thought it was acceptable that our world have billionaires who hold more money than over 50% of the people in the globe. Our normal was already a crisis.

The hypocrisy (it’s ok to be angry)

Our hypocrisy is being exposed right alongside our systems. The gaping hole in a country without healthcare as a human right, without a centralized system, in America has never been clearer. The distrust sown by politicians in the climate crisis has caused a terrifying lack of trust in scientists for those who lean right in countries across the world. It is now laying bare the consequences (and plenty of conspiracy theories) of this.

Watching the Prime Minister of the UK, Boris Johnson, stand and clap for the National Health Service (NHS) after downplaying the virus, campaigning for Brexit, and the reigning conservative party of the last ten years wanting to hamper the service, is difficult to swallow. In recent years Boris voted against lifting the 1% pay-rise cap for NHS nurses and cheered when a pay rise for nurses was blocked. The UK was already short over 40,000 nurses before the crisis (not helped by mass exits over Brexit) and had less doctors than other similar countries per person in Europe (and not due to a healthier population). I lived in London a decade ago when BoJo was mayor. I loved the NHS; it was something of a miracle. Watching it being used a stick by conservativesto leave the EU (as a slogan for “saved funds” that was proven inaccurate) and their actions since has not been pretty.

The hypocrisy is everywhere.The most defiant defenders of a ‘free market’ are asking for government handouts. I personally know many people who have argued angrily for conservative politics over and over again. Who argue against welfare constantly. Who believe you get exactly where you are on your merits only and that if you’re not ‘making it’ it’s because you’re not working hard enough (an entirely disproven theory). Those same people voted governments in to aid their mortgages and retirement funds, ignoring all the women in their lives, the refugees, the migrant workers who support jobs they would never contemplate, those who have been raised in a system of poverty and people of color. None of it was important. Until of course they lost their job and couldn’t pay their mortgage. Then the government needed to immediately step in and bail them out. Until the renters in their two investment properties couldn’t afford the rent because they suddenly lost their own jobs.

Governments who have utterly refused to action things such as equal parental leave, significantly reducing child care costs, trialing some type of universal basic income, increasing the minimum wage, or ensuring free healthcare for all; literally any policy that meets human rights and/or decreases the inequality we all live within, often calling these socialist policies, are now acting as socialist bodies.

Companies that have constantly denied flexible working hours, remote working and reduced working weeks to accommodate children, volunteering, running other projects, cooking fresh meals, studying, and wasting less are suddenly enforcing all these measures.

It’s ok to be angry at this. It is ok to let that anger flow through you. To run it out. To yoga it out. To art it out. Let it in and then let it out.

The hypocrisy between the two crises of climate change and this pandemic too is of course dumbfounding. Only a few months ago we were talking about Australia’s horrific reaction to the Pacific islands going down (quite literally) with climate change to which Australia, the third largest exporter of fossil fuels on the globe with the biggest homes in the world, contributes far more than its fair share per capita. It was only earlierthis year that the Deputy PM of Australia stated through his smugness “I get a little bit annoyed when we have people in those sorts of countries pointing the finger at Australia and saying we should be shutting down our resources sector so that they will continue to survive. They will continue to survive because many of their workers come here and pick our fruit.”

Tuvalu’s Prime Minister retorted “you are concerned about saving your economy in Australia, I am concerned about saving my people in Tuvalu”.

Only a couple of months of burning bushfires later and the Australian Prime Minister – previously missing on climate action – is now declaring that he has “explained to G20 leaders that our Pacific island family must be a focus of international support. We are re-configuring our development assistance to ensure critical health services can continue to function and to help our Pacific neighbours and Timor-Leste to manage the immediate economic impacts of the pandemic.”

The country is willing to lend a helpful (media) hand with the current pandemic because its economy has also been thrown into the gutter with everyone else’s. In terms of the climate however, when there is oh-so-much money to be made by selling a never ending supply of resources, there will be no help. Economy over environment.Never understanding of course that the environment runs perfectly fine without an economy but the reverse is not true. The previously fired Director of Tourism Australia (that’s the Australian Prime Minister) has now found himself handing out money left, right and centre, where previously there was not even a desire to pay firefighters, as he attempts to save his voting constituents from the grips of death, jobs losses and stock market wipeouts.

We are all hypocrites, constantly. The system makes it so. But hypocrisy on a level like this is different. It impact lives; many millions of them. And it puts an ideological choke hold on us the rest of the time. It needs to be called out consistently, and loudly, and it needs to force changes and an action for what we really value.

Corona vs the climate

Where does that all leave us in environmentalism? The comparisons with corona and the climate can seem apt but there are key differences between them which serve to explain why we have acted on one and not the other.

- Coronavirus is imminent, climate change is not. It is of course, people are already suffering and dying, but to most of us it doesn’t feel that way.

- Coronavirus feels like it might happen to you, climate change feels like it will happen to somebody else.

- Any reduction in lifestyle due to coronavirus is perceived as temporary and it will ‘go back to normal’. Changes in lifestyle for the climate crisis feel permanent.

- Coronavirus still feels stoppable (and politicians are short term focussed and will feel consequences at the voting booth). Climate change feels inevitable to many who will be living through it (and today’s politicians won’t be in power and in most countries aren’t incentivized for long-term strategy).

- The media is in an absolutely frenzy about the virus. Large parts of the media often ignore, spin, underplay and deny the climate crisis. Give us the death and affected ticker for climate if that’s what causes us to act.

- Coronavirus largely requires us to address the virus and the healthcare system. Climate change requires us to address the resulting environmental catastrophes, and racism, sexism, colonialism, poverty, justice, and inequality. Of course this virus is also intersecting with a number of these systemic issues (horrifically so) but we do not have to solve them in order to resolve the pandemic. We do in climate change if we want the world to go on with more than a few rich men. The economy cannot simply bail everyone out without implementing just policies forever; it can only do so as temporary measure.

- The societal response to coronavirus is to stockpile food, toiletries and other items. The required response to climate change is to reduce our consumption in industrialized countries.

- This one is still to be determined but if the 2008 recession is anything to go by, we will bounce back from the economic shock of coronavirus after some time. The long term impact is likelier to be negligible. Climate change is not priced into the stock market at all, has long terms impacts, has plenty of unknown-unknowns and positive feedback loops, and is unpredictable.

You can swap out climate change in all those with the biodiversity crisis. It’s even less prominent (far less) and just as important as the climate crisis.

Coronavirus has so far even had a direct impact on our knowledge of climate change. It has already forced the cancellation of two NASA missionsand field expeditionsin the Arctic meant to study sea-level rise, extreme weather and changing Arctic conditions to inform climate models. Due to travel restrictions, the expeditions will be delayed resulting in data gaps that may affect the accuracy of our climate models. The COP26 meeting that was due and highly anticipated on countries action for change has also been delayed.

So, what we can learn for the climate crisis?

It is now clear that we can immediately change our entire lives when we have the will too. We can reduce emissions within a day when we believe we need to. We can drastically alter the entire way knowledge workers work from corporations across the globe. We can suddenly pay people to not work – just like in a universal basic income arrangement (but these payment arrangements have been far more generous in European countries) – and those people can keep their homes, volunteer, be creative, cook and spend time doing real things. It is now obvious that we can in fact listen to scientists; even people who have been deriding them for years. It is also clear the perils it causes when we don’t listen to those same experts for the first decade in order to prepare and mitigate (and we’re already five decades in for ignoring climate scientists). It turns out we can easily consume less fast fashion and household goods. We can travel less. We can slow down construction and shut up factories. We can do a whole lot just within a few weeks.

Imagine if we had a clear transition plan where we could create an incredible and sustainable future where we roll these things out comfortably in a way that promotes positive life rather than shattering our existence?

Can we transition to that now? Can we sell this story of the future? I am still entirely uncertain about this. Will this pandemic destroy the gathering momentum we were creating or will it accelerate it?

I don’t know. I’ve been here before and I’ve been burned (maybe like you?). 2008 was the year everything should have changed. Wall Street was bailed out. The public was mad. There was an exciting new leader. Banks were detested. Economists were not our saints nor saviors. All it needed was a vision & strength. Mobilizing a groundswell wouldn’t have required mass change. The feelings had already been stoked. We didn’t of course. We played it safe and ended up in the same spot with the same problems, returned to the same policies, and found barely a lesson in sight. Growth-on-growth-on-growth with ever increasing consumption.

Our problems were never technical anyway (aside from industrial heating). We already knew – we still know – everything that needed doing and we had all the technology and human skills to do it. We just weren’t willing to. Many of us have been far too happy living life exactly as we did hoping new technology would arrive and suck us out of the mess without us having to alter anything in life. Covid-19 has shown us that in a matter of minutes it turns out we can do it ourselves.

Can you fathom suggesting a shut down of numerous manufacturing, service and airline industries in order to flatten the curve of the climate crisis? Can you imagine how much you would have laughed at the notion that governments would tell their citizens to stay home and small businesses to shut up shop? That in European countries, they would pay for it? That we could no longer not just not touch each other, but be nowhere near each other? That we were forbidden from it?

A few months ago all of this was absurd. We haven’t enacted any drastic measures in the fifty years we have known about Anthropogenic climate change. Now, within mere weeks, it’s our reality.

Here’s what else we learn

x

- No matter who is more responsible or who is more at fault, we all suffer.

- The poorest and most vulnerable will suffer most. We are only as safe as our most vulnerable (hat tip to Bernie Sanders).

- Systemic issues are everywhere. They’re where we’re looking most, and they intersect with everything we work on. In this pandemic alone we’re seeing more evidence of our factory farming, urban growth and capitalism being part of the root cause and we’re dealing with the fall out of poverty and inequality.

- We need to price in risks much better. We seem to do most things for economical reasons not moral ones but let’s take that. Project Drawdown has quantified and compared the upfront costs of deploying climate solutions to limit warming to up to 2 degrees celsius with the long-term savings from avoiding climate breakdown. The key conclusion is that while the upfront costs are substantial – around $USD 25 trillion – the resulting savings and profits are four to five times larger, at around $USD 145 trillion for the globe. That figure doesn’t even account for the additional value of climate action, including healthcare savings from reduced air pollution and avoided climate damages (e.g. agricultural losses).

- Consistent messaging from leaders in government, community groups, and companies are able to create cohesion. Enforced policies for issues of major risk then back these up. Too often in biodiversity policies for example we simply ignore them and completely neglect to enforce them. Let’s create a police state for environmental destruction if we’re going to have one. Let’s use our enforcement powers for good.

- There’s no longer an easy curve to flatten in the climate crisis, we’re already locked into a number of outcomes, but we can sure as hell do a lot more and it would save millions of lives. Sadly three word slogans really do seem to work (flatten the curve). Maybe we need one for the climate (environment over death?).

- Many businesses can entirely change the way we work within the space of a few days; even those who have resisted it longest.

- The most conservative and hypercapitalist of countries have no real ideological problems with socialist policies when faced with a crisis they deem detrimental to themselves. We should point this out and force it more in necessary climate action.

- Politicians will act far more if they believe it will directly affect their own lives or block them in the voting booth from re-election. They’ve proven they can listen to scientists now when scared enough; we need the same for climate science.

- Prevention is better than cure. So, so much better in every way.

- There is stark contrast between western European and advanced South Asian systems such as Taiwan, Thailand and Singapore, positioned against places like the USA for health care. For some reason we often ignore how well many Asian structures run and rarely are they used as common examples. Let’s do it more.

- It turns out we can listen to scientists even when we haven’t for decades.

- Division sows doubt so it’s important to be transparent in what we do and say all the time and outline facts clearly and in a well informed manner. It’s important to explain why we’re doing the things we do in a democracy (use Angela Merkel’s speechas an example).

- People are, on the whole, really terrified of pandemics, and climate change can potentially increase the likelihood of these.

- Would-be dictators are everywhere and consider power grabbing their opportunities in a crisis. Look at Hungary and Cambodia. Think about how China acted. We’ll need to watch this as the climate movement develops more policies and strategies.

A note on sexism

We know climate change will affect women disproportionately. Even though coronavirus seems to affect men more directly, the Covid crisis itself is likely having a bigger impact on women. The majority of nurses on the front line are womxn. Most flight attendants, teachers and workers in the service industry such as cafès and restaurants, all who are losing their jobs, are female. Most aged care staff are women. Many women have spent weeks working, looking after children no longer at school and still organizing care for their parents or parents in law as women make up the largest portion of unpaid care. Domestic violence is escalating across the world even while it’s simultaneously harder for women to report it with their partners at home. Spending more time at home may also reinforce stereotypical gender roles. This isn’t to say men are not suffering. They absolutely are. It’s just that the climate crisis affects women more in a whole variety of indirect ways, and we’re seeing it play out here too.

Just for fun: In the most clear and bizarre display of overt sexism, the Australian government allowed hairdressers to stay open but limited all appointments to thirty minutes (even though experts point out you need fifteen minutes of contact time for transmission). Effectively it ruled out women from the salon but allowed men to get their hair cut. Only a group of middle-aged men could make that decision without considering what it means in practice (and then had to scrap the rule).

A note on poverty

We also know that in nearly every crisis, those who live in lower-income countries and vulnerable communities are hit the hardest. Already at a major disadvantage – structurally in terms of assets, income, access to education and opportunity, employment, a history of colonialism and/or racism and more – every weight on top of this hits disproportionately harder. A few thousand dollars matters more to somebody on a $23,000 salary than somebody earning $85,000. Physical distancing is also a privilege. Nearly all of those who live in poorer regions are not able to practice this with housing closing together and more occupants in one house. In the region we work in in Cambodia we have no access to running water – how are people going to regularly wash their hands for twenty seconds with soap and sanitizer (we don’t have) without water? Or are we all going to do it in the toxin filled river? We also know that in numerous countries that don’t have equal (and free) healthcare for all, those who are poorer also have less access to quality health care, higher exposure to pollution, are further away from food and medical services, and certain diseases are more prevalent. It’s likely why in New York the highest incidence of cases is in more vulnerable regions like Queens. And this new piecesuggests pollution plays a large role in corona deaths; just as it does in our consumption crisis.

A small note on racism

Due to the systemic issues we have across the world we also know crises affect people of color more. Communities of color are often in more vulnerable positions prior to a crisis, and a crisis therefore has a disproportionately larger impact. In this particular pandemic, many people of color cannot afford to give up or lose their jobs and stay home. We see non-subtle racism appear when government ministers refer to the Chinese or Wuhan virus and it’s specifically for this reason that the World Health Organization (WHO) now has a best practicein place for naming viruses. In places such as America where there are already significant racist issues within healthcare, we’re probably going to start seeing more in the care provided too. African Americans are, for example, more likely to be denied testing and treatment. This is also why disaggregated data is so important. The Black population of Illinoismakes up 14% of the state, but 41% of the deaths so far have been Black people. In Louisiana, African-Americans makes up approximately 32% of the population, but 70% of the Covid deaths so far (correct at time of writing).

“Out of all the disparities caused by the inequities in our society, healthcare might be the most inhumane, and I think this pandemic of 2020 magnifies that truth.” – Rev. Dr. Marshall Elijah Hatch Sr

All of this to say, there are overlapping sections of this current crisis that we know are already the same in the climate crisis. We need to acknowledge that as a globe and specifically – and differently – act on these issues.

The end & beginning

As you can probably read between the lines of this piece, I am still bouncing between hope and heartbreak. I am a positive person andrarely feel a genuine sense of hope for the world I’d like to envision. I’m buoyed by the goal to reduce suffering in the very small capacity I can and don’t require hope to take action. It’s even odder to feel hope in such juxtaposition with the heartbreak of all those who are losing businesses they’ve worked their backside off for, for children that will be so detrimentally impacted, and for women who will now be trapped in a cycle of violence indefinitely.

If the world is going to crash into another economic crisis we cannot wastethis opportunity again. We need to place deforestation, and a reduction in land-use change, pollution and consumption, as priorities. A renewable only strategy (which we aren’t even pursuing in many of the deals saving conglomerates) isn’t going to cut it at all (though we still need this as one prong of many). Money needs to be pumped into regenerative agriculture, into transforming communities, into fundamentally changing the way we work and the way we live. Entire industries can be reshaped. We can relocalize wherever practical. And many of us can also learn to use less, waste less, grow our own food, share, create more, and focus on things that matter. Recessions are extremely painful and affect all of us but the poorest bear the biggest burden. We should be sending significant money into alleviating poverty, social injustice and suffering for the under-privileged.

We have the opportunity now to completely change the world. This is usually the time that creativity and policy innovation shines and I’m excited to see it happening. As I go to publish this, Spain is considering a permanent Universal Basic Incomeand Amsterdam is implementing Doughnut Economicsheading out of the crisis. It is possible and our climate solutions are also solutions to moving out of this pandemic.

More than anything, we have been warned for years that we are well off course to meet our goals. This will be one of our final opportunities to find the way forward. The way in which we recover from this pandemic needs to be entirely aligned and entangled with how we deal with the climate crisis. It might even be our very last chance.

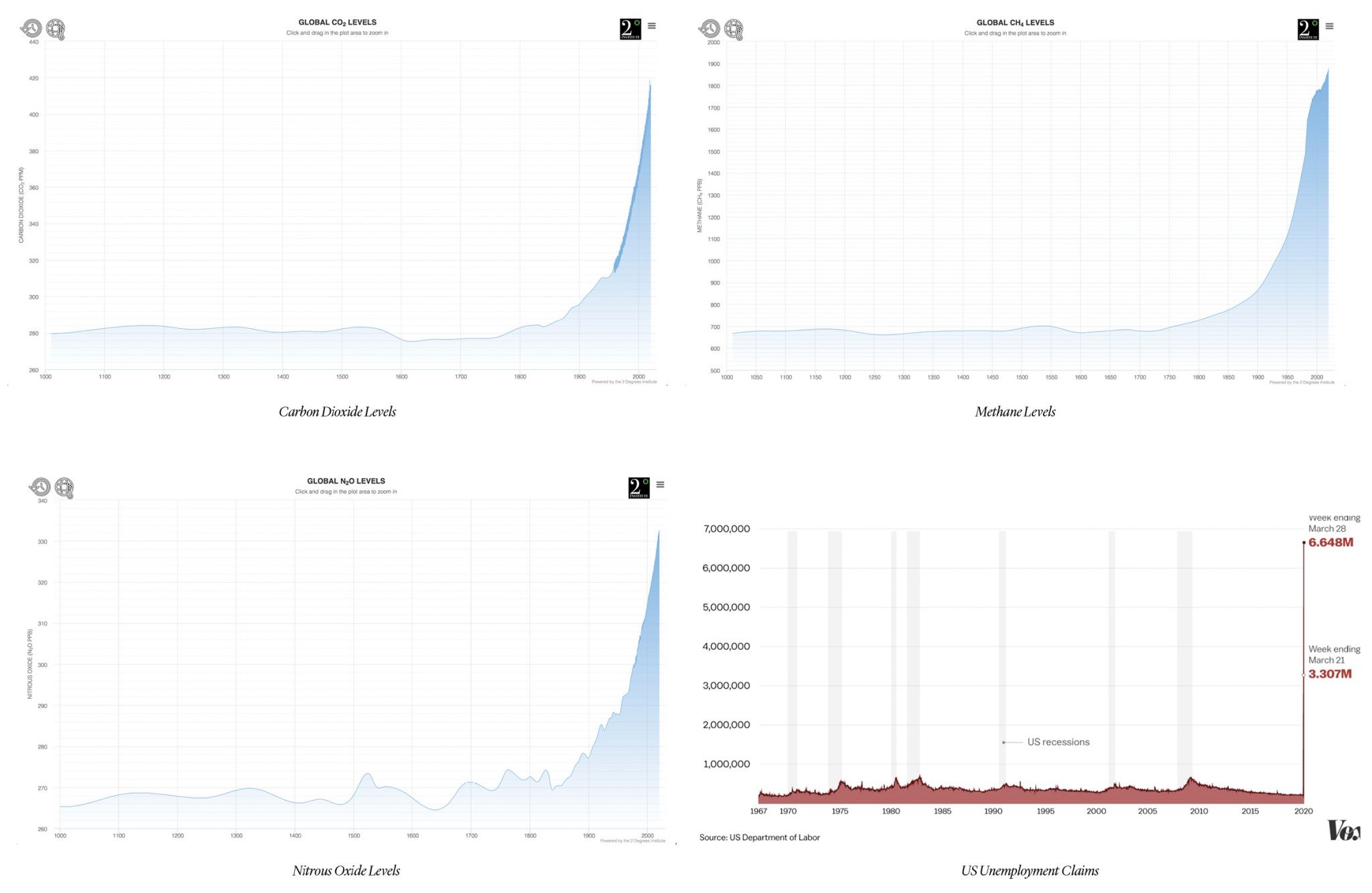

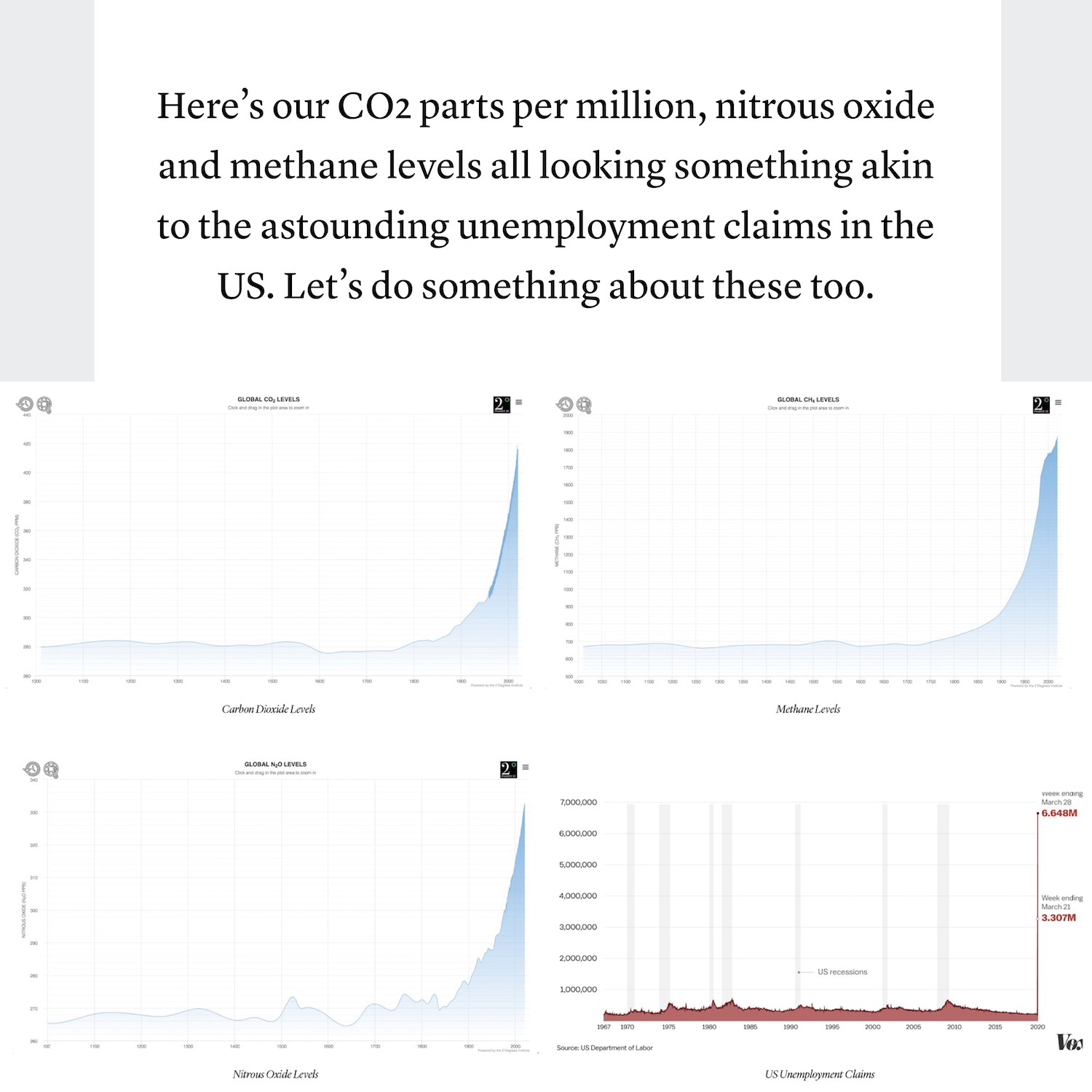

To end, because we all like staring at graphs now, I’ll leave you with a final ‘curve’ (it’s not) that need addressing.

Here’s our CO2 parts per million, nitrous oxide and methane levels all looking something akin to the astounding unemployment claims in the US. Let’s do something about these too.

P.S. Prefer a Linkedin version of this piece to comment or share? Find it here.