Free Guide

Your first guide to biodiversity

- Part One

The biodiversity crisis is happening right alongside the climate crisis. Both influence each other and yet we’re often only speaking about one. The biodiversity crisis is under-discussed and misunderstood. In this three part guide we’re digging into what it is, the scope and cause of the crisis, and how we all contribute and can help.

What is biodiversity?

Whenever we speak of biodiversity, we are speaking of all life on Earth or all living beings. When you hear biodiversity crisis, think wildlife crisis or nature crisis.

Biodiversity is us, it is the bacteria that reside in our bodies, it is every animal, plant, microbe on this planet, and anything in between that carries the spark of life in the form of DNA. Biodiversity can be understood as the variety of different genes, species and individuals of a species in any given area, from the global to the microscopic scale.

For a small example of biodiversity “inception”, look no further than the termite! They have one of the most biodiverse communities of microbes residing within their guts (microbiome). Not only do termites have tiny organisms called ‘protozoa’ living in their guts that help them digest woody fibres, these protozoa have small bacteria living within their ‘guts’ – biodiversity within biodiversity!

The variety and variability of living organisms contributes to the stability and resilience of ecosystems and our modern society.

We humans are part of, and fully dependent on, this web of life: it gives us the food we eat, filters the water we drink, and supplies the air we breathe. Nature is as important for our mental and physical wellbeing as it is for our society’s ability to cope with global change, health threats and disasters. We need nature in our lives. – European Commission

Scientists estimate there are at least eight million different plant and animal species on the Earth, 5.5 million of which are insects. However, if this number included microscopic organisms like bacteria, phytoplankton, zooplankton, archaea, fungi, and protozoa, the number would likely reach near the trillions (more than the stars in the Milky Way).

According to a 2019 global biodiversity assessment, 86 percent of existing species on Earth and 91 percent of species in the ocean still await description (i.e haven’t been named, quantified or studied yet).

From the world’s great rainforests to small parks and gardens, from the blue whale to microscopic fungi, biodiversity is the extraordinary variety of life on Earth - The European Commission

Why is it so important?

Well for one, without biodiversity, humans wouldn’t exist, and Earth wouldn’t be Earth! It would be like the Moon, or Mars.

Living beings in all of their diversity are responsible for the oxygen in our atmosphere, the ozone layer that protects us from the sun, the soil that grows our food and fibre, the forests that filter our air and water, and the microbes in our body that enable us to digest food.

Secondly, biodiversity is beautiful – it has intrinsic value. Each living creature earned their right to be on this Earth, surviving through millennia of evolutionary hurdles to enable their descendants to exist today.

Thirdly, biodiversity equals resilience.

We all know that it is better to eat a diversity of foods, it is better to have a diversity of peoples and cultures and points of view in the room, it is better to have a diversity of different industries and job opportunities for a resilient economy, and better to have a diversity of different tools in your toolbox. Why? Because it means there are options and solutions for when something goes wrong; it means the weaker members of the group can rely on the stronger ones to keep things going whilst they recover; and it means there are a multitude of different strategies and solutions for forging a new, innovative pathway.

Ecosystems that have a greater number of different species playing different important roles are better able to resist disturbances and adapt to change. There is safety and strength in numbers, and opportunity in diversity.

Is biodiversity declining?

In 2019 the most comprehensive assessment of global biodiversity ever completed was released by an organization called (get ready, it’s a mouthful), the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). The report (a massive collaborative effort between 455 authors) concluded that around one million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction, many within decades.

This is across all species groups – including plants, mammals, insects, amphibian, marine organisms (though data on microorganisms like bacteria and fungi is missing). The rapid loss of species today is estimated by experts to be at least 1,000 times higher than the natural extinction rate.

It’s important to remember that these numbers represent real living, breathing beings, and these findings are averaged across entire animal groups. Averages obscure the peaks, and some species are experiencing dramatically worse rates of decline. Due to the interconnected nature of ecosystems, losing one species could result in the complete collapse of the entire system, leading to subsequent cascading extinctions (like a domino effect). Here’s some other key findings from the report:

The biosphere, upon which humanity as a whole depends, is being altered to an unparalleled degree. Nature is declining at rates unprecedented in history - and the rate of species extinctions is accelerating. - Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)

What threatens biodiversity or causes biodiversity decline?

In short – the growth and dominance of our species over almost every corner of the planet, and more importantly, our creation of a system of consumption and trade that is extractive, wasteful and far overshoots what the Earth can sustain.

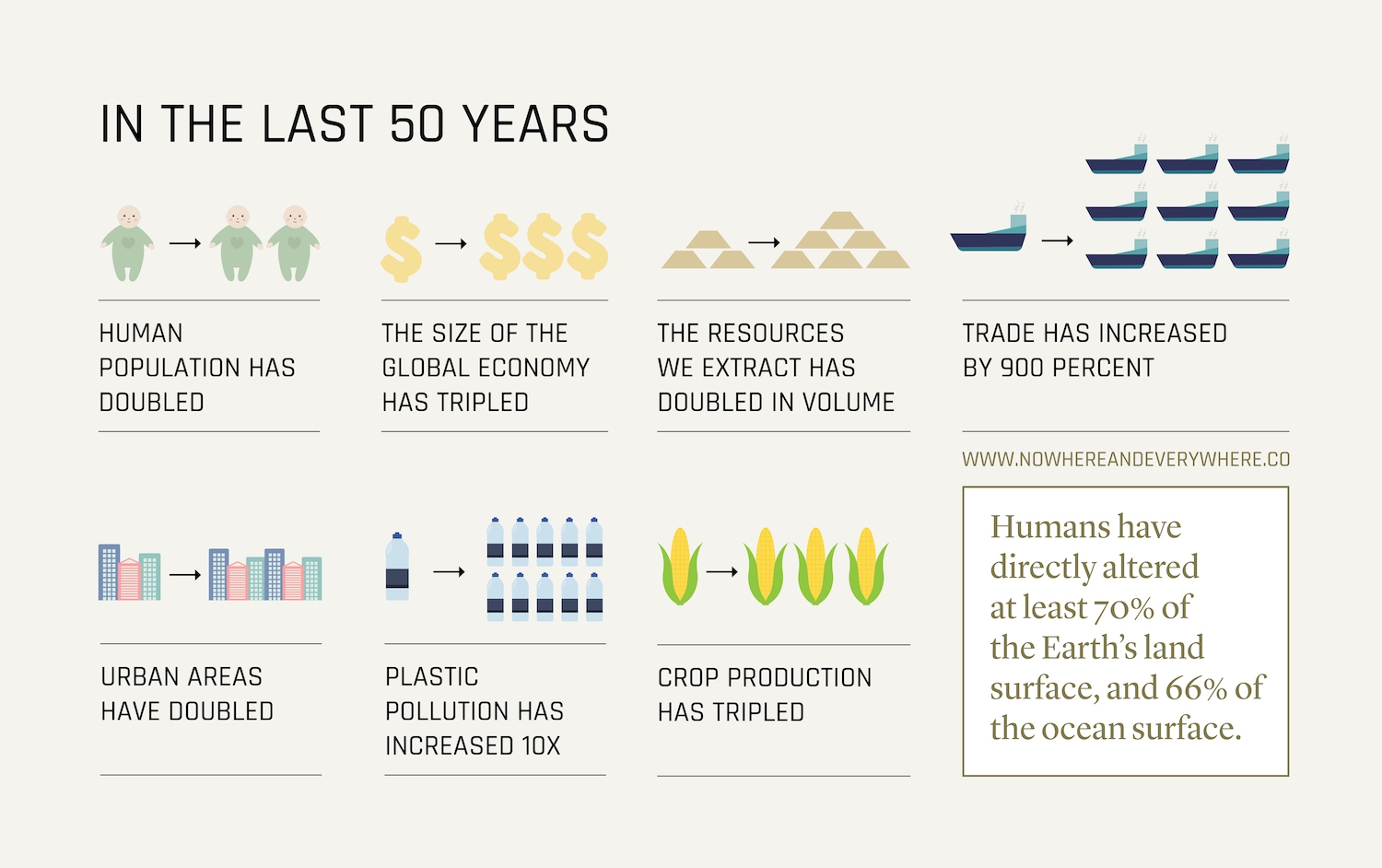

The largest driver of biodiversity loss on land has been the conversion of pristine native habitats into agricultural systems to feed the world. This has been driven in large part, by a doubling of the world’s population, a three-fold increase in the global economy, doubling of the resources extracted (renewable and non-renewable), a ninefold increase in trade, doubling of urban areas, a ten-fold increase in plastic pollution, and a three-fold increase in global crop production- since the 1970s.

Humans have directly altered at least 70% of the Earth’s land surface, and 66% of the ocean surface is experiencing increasingly negative impacts (deep water environments are less studied and therefore less understood). As a result, the area of undisturbed natural habitat for wildlife is rapidly shrinking.

85%

of wetland area (important habitat, water purification and carbon storage) has been degraded since the pre-industrial period, and drained or developed for agriculture or urban areas.

77%

of rivers longer than 1000 km no longer flow freely from source to sea, either modified by dams or over extracted for irrigation.

50%

seagrass extent has declined this much since 1950 (another important natural habitat and carbons store); decreasing by more than 10% per decade.

50%

Live coral cover on reefs has nearly halved in the past 150 years and is projected to virtually disappear this century.

There are 5 key direct drivers of biodiversity loss

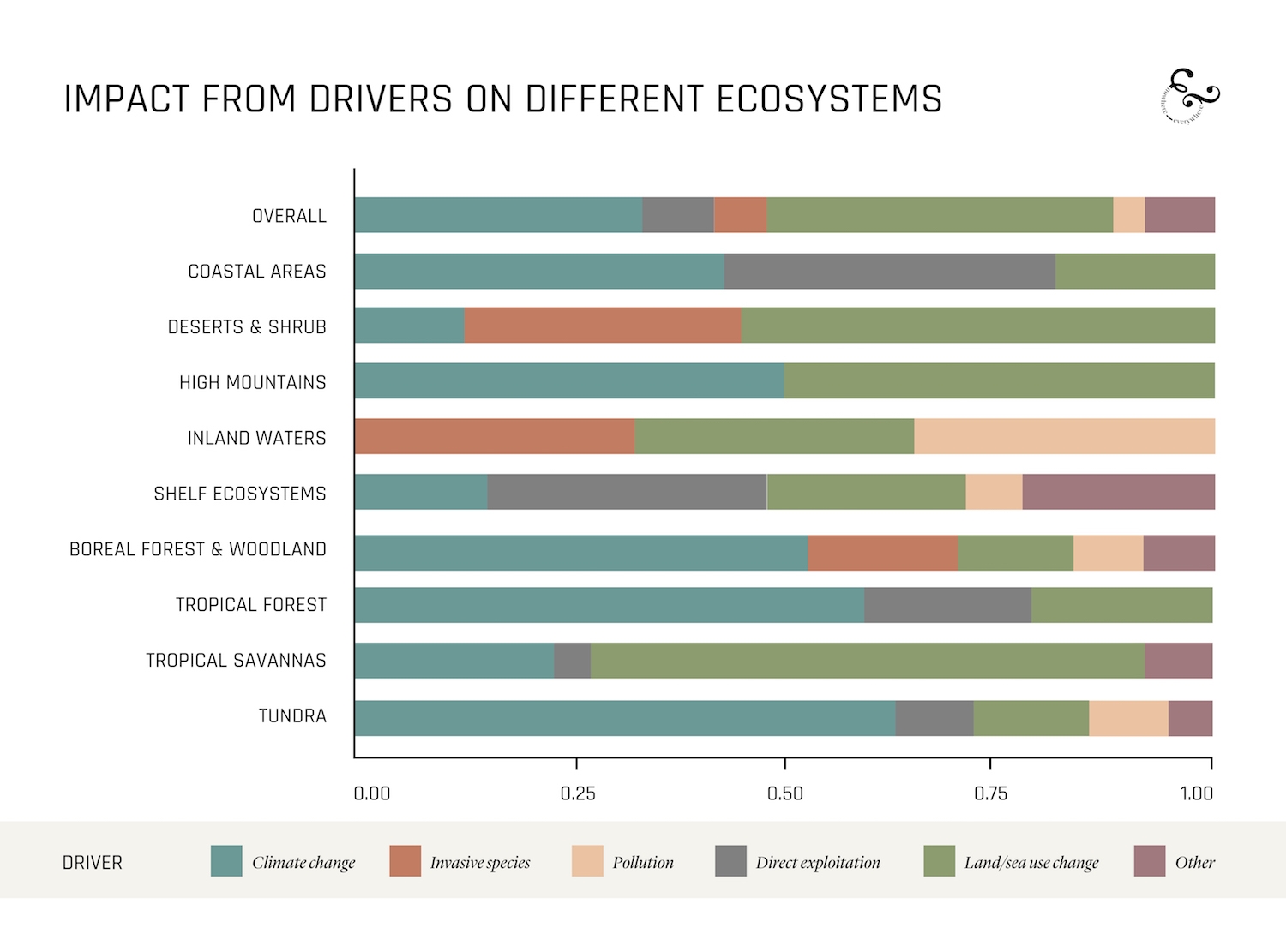

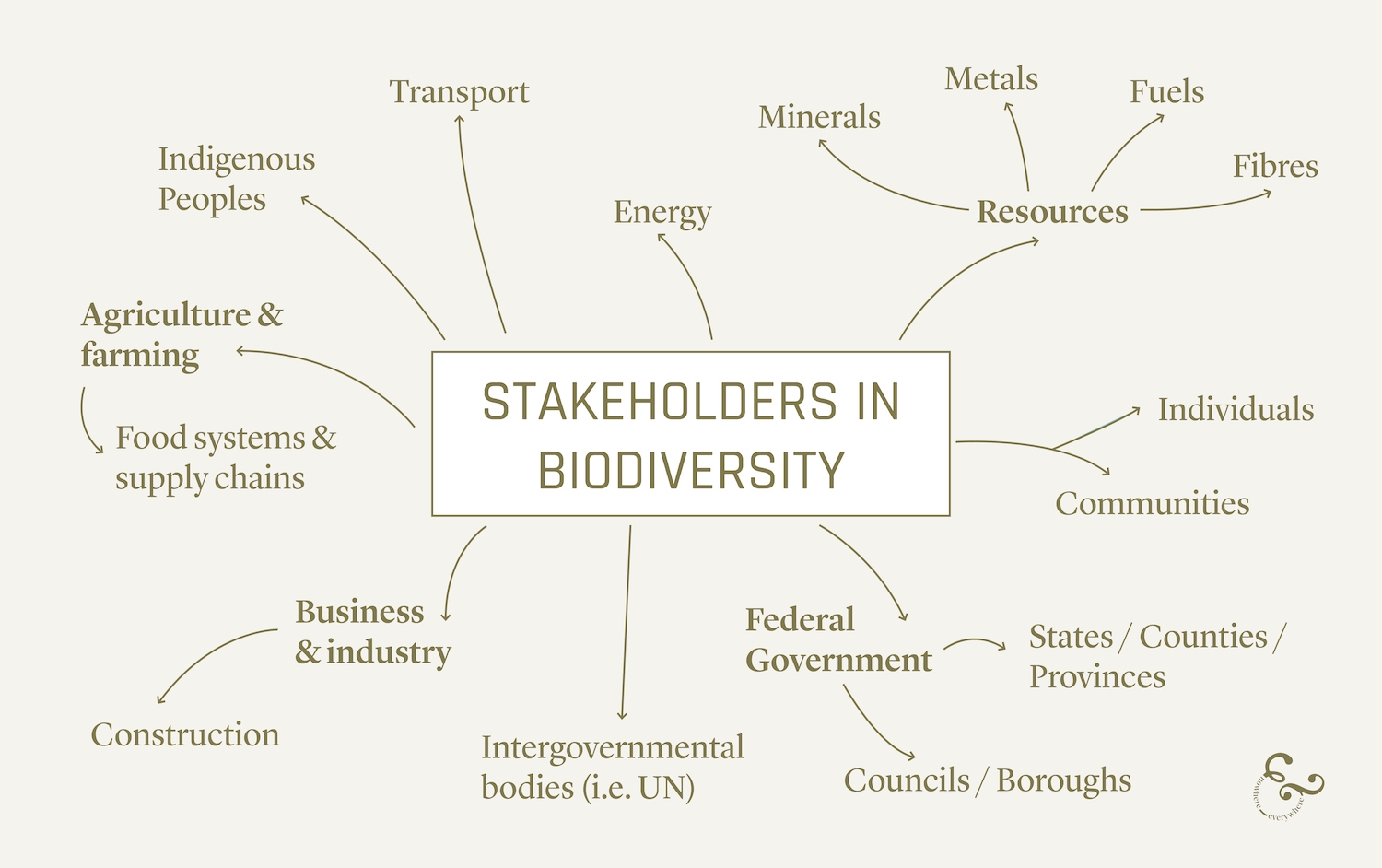

The causes of biodiversity loss are many, varied and interconnected. To make sense of this vast problem, IPBES has identified the five main human-driven causes behind nature’s decline, which are: changes in land and sea use, direct exploitation of organisms, climate change, pollution and invasive species. When we say ‘human-driven,’ it means that these causes are the direct consequences of our specific way of living and consuming resources on this planet.

1

Changes in land and sea use

Humanity is a dominant global influence on life and ecosystems on Earth, having created an unbridled, inequitable economic system that pushes for exponential growth where most can’t meet basic needs, and the rest have so much that they throw resources away.

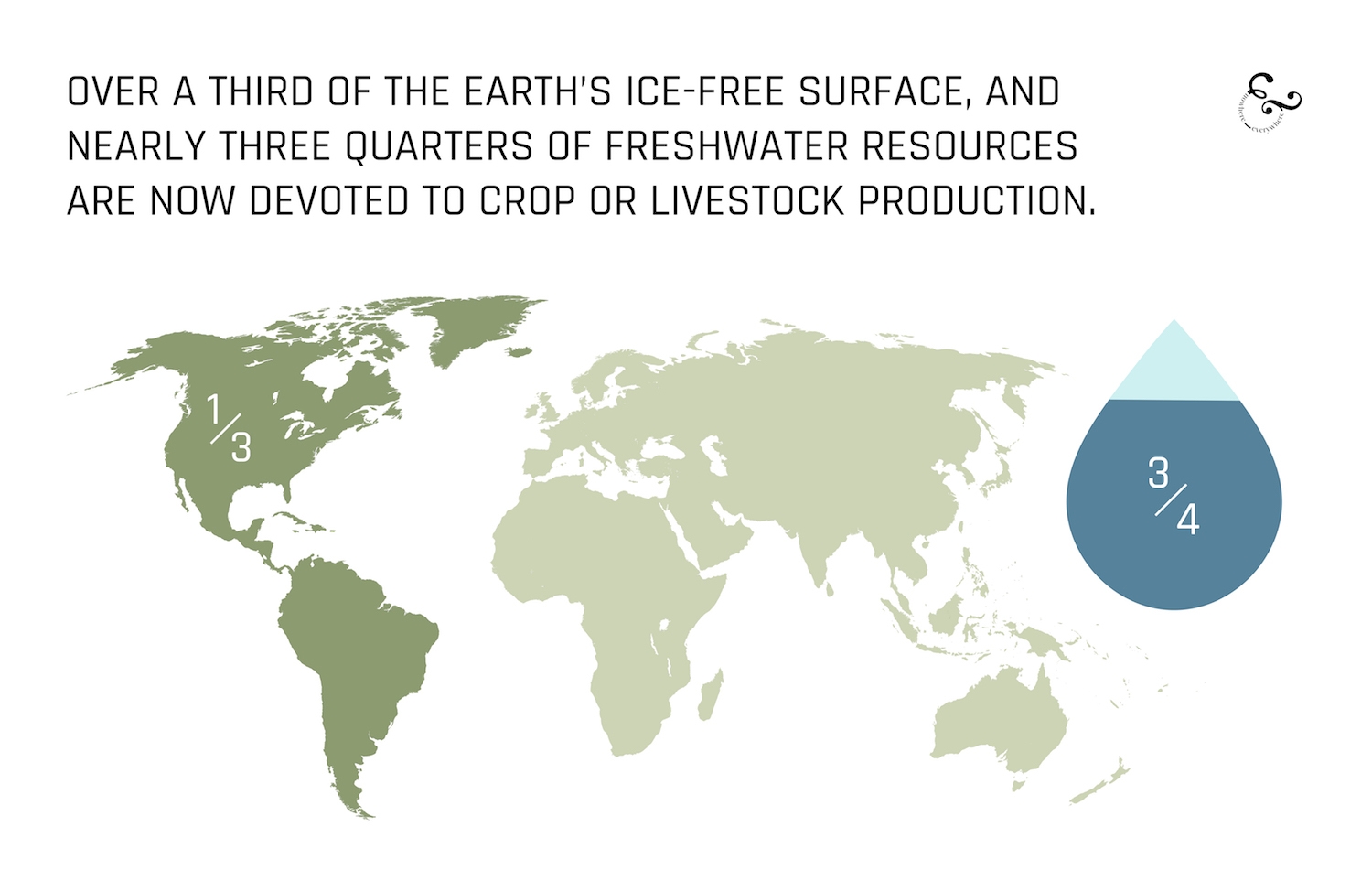

This is most evident in our food system, which has the largest direct impact of all human activities on biodiversity. Over a ⅓ of the Earth’s ice-free surface, and nearly 75% of freshwater resources are now devoted to crop or livestock production, with the most recent clearance of native habitats being concentrated in some of the most species-rich ecosystems on the planet.

From 1980-2000, 100 million hectares of tropical forest (approximately equivalent to the entire land area of China!) were lost, mainly from cattle ranching in Latin America and palm-oil plantations in South-East Asia. Once bustling areas of biodiversity (in rainforests, a single tree can support hundreds of other plant, animal and insect species) have been converted to single-crop monocultures of corn, soy and grains that can’t support insects or other plants.

2

Direct exploitation of organisms

Direct exploitation of organisms can be for the purposes of obtaining food, such as fishing or hunting. However, due to the size of our population and the greed of a select few, we are exploiting organisms beyond meeting our basic needs.

Over-exploitation is evident in overfishing (using trawl-nets that capture anything in their path); poaching for fur, ivory, and plant/animal products for traditional medicines (such as Pangolin scales, bear bile and rhinoceros horn); the illegal (and legal) live animal trade for exotic pets (see the controversial Tiger King series on Netflix); the collection of coral, shells, exotic feathers and tortoise-shell for tourism trinkets; and hunting for sport (such as trophy hunting, duck-shooting, spear-fishing and sport-fishing).

3

Climate change

Climate Change is an additional pressure that exacerbates the impact of all of the other drivers (more on this in Part 2).

4

Invasive alien species

The globalized nature of our world means that species have been able to migrate to new geographical areas like never before. The number of invasive alien species per country has risen by about 70% since 1970. ‘Invasive’ species are thus called because they evolved separately to the regions where they have been recently introduced, and therefore ‘disrupt’ the balance of ecosystems and their food chains. For example, Australian ecosystems and biodiversity has been decimated by the introduction of species such as the cane toad, the European fox, feral cats and dogs, rabbits, and hoofed herbivores such as deer, sheep, cattle, camels and donkeys with the advent of colonization. Native Australian animals are suffering devastating declines due to predation, food competition, poisoning, habitat degradation and disease-transmission from invasive species.

5

Pollution

Plastic

Over 10 million tonnes of plastic enter the ocean each year through deliberate dumping, or carried there through waste in unfiltered stormwater or high winds. Plastic is present in every corner of our lives, but the strong physical properties that make plastics useful also make them extremely difficult to biodegrade in the environment. The plastics end up blocking the digestive tracts of marine animals, compromising their ability to digest food or adjust their buoyancy, thereby leading to starvation. Microplastics also absorb toxic pollutants and foreign bacteria, which are absorbed into an organisms’ tissues after ingestion and concentrated up the food chain. These pollutants absorb into fatty tissues of marine mammals, inadvertently poisoning their offspring through their toxin-laden milk.

Chemical Pollution

300 – 400 million tonnes of heavy metals, solvents, toxic sludge and other wastes from industrial facilities are dumped annually into the world’s waters, either directly poisoning species or disrupting their brain function and their ability to reproduce and migrate. The overapplication of fertilizer in large agriculture operations means almost 50% of it is washed into the environment, entering rivers and coastal ecosystems. This has resulted in over 400 seasonal dead zones in the ocean (covering a combined area greater than that of the UK), where bacterial decomposition of algal blooms depletes oxygen supply from the surrounding water, essentially suffocating marine life.

What drives the drivers? What or whom is to blame?

All of us (that’s sad, but keep in mind that it also means everyone can play their part in turning things around). However, some of us are more culpable than others. The loss of biodiversity is fundamentally tied to our economic system and the inequitable distribution of wealth and resources amongst the human species.

We will never address the impacts of biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation without addressing the deeper causes. Why are people driven to poach animals, and to clear land to plant crops? To make an income.

What is driving the demand that establishes these practices as a source of income? Overconsumption and inequality.

We can blame biodiversity loss on big, bad companies, but all of us individually drive the demand that in turn, drives the unsustainable cycle of production and extraction of the Earth’s resources.

Other systemic drivers include:

- Opaque and geographically dispersed supply chains that separate consumers from producers

- Unregulated economic growth

- Failure of policies and institutions to incentivize sustainable practices and enforce environmental protections

- Overconsumption, our constant need to upgrade, and our ‘throw-away’ society (deliberately created by marketing and social status norms)

- Profit and shareholder incentives

- Inequality

- Short-term election cycles

- Human behavior that is programmed to prioritize short-term survival over long-term consequences

- Linear view of the world that fails to see the world as an interconnected system

- Disconnection with nature

Stay informed

We only send out awesome, helpful environmental emails every two weeks and never spam. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Terms to know

Biodiversity

Whenever you see this word, think wildlife or all living beings (apart from humans); all the plants, animals and ecosystems.

Biodiversity hotspot

An area with a very high number of different species or a high number of species unique to that area.

Endemic species

A species that is native or unique to a certain region or country and isn’t found anywhere else. This species evolved in and survives in a very specific area, and is therefore often threatened with extinction.

Genetic diversity

The variety of genes (DNA) within an organism, a species, a population and a community of different organisms. This variety allows individuals and ecosystems to tolerate and adapt to stress caused by changing environmental conditions.

Habitat fragmentation

When a large area of intact ecosystem (e.g a forest) is cleared gradually over time into smaller, disconnected patches. This can alter the ecosystem’s climatic conditions such as temperature, wind, humidity and light availability and can also disrupt the migration, foraging and hunting behaviour of animals.

IUCN Red List

The world’s most comprehensive list of the global ‘conservation status’ of plant and animal species, which indicates the severity of their risk of extinction.

Keystone species

When we think of species like nodes in an interconnected web – keystone species are the nodes that have the most links and are most critical to the survival of others in the web. Without them, the ecosystem would no longer function or would be drastically different to its current form. Example – coral, sharks, wolves, bees, earthworms.

Umbrella species

Similar to a keystone species, umbrella species are linked to countless other species. They are often chosen for protection, because protecting them indirectly conserves the species that depend upon it.

Rewilding

The preservation of a degraded landscape from human activity with the goal of restoring it to a prior natural state. Rewilding aims to restore natural processes by reintroducing keystone animal species that once lived in the area, rather than more active human intervention.

Restoration

The process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, or destroyed through active human intervention such as planting vegetation, clearing weeds or removing invasive species.

Why is biodiversity loss bad?

Entire ecosystems can collapse

In an ecosystem, different species play different important roles: For example, trees and other plants not only provide food, but also create ecosystem structure and shelter; insects are important sources of food for birds and reptiles but also control the overgrowth of vegetation in their role as consumers; consumers and predators control the populations of insects and also create nutrients that fertilise the trees and spread their seeds. A diversity of species, many of them performing the same role in the ecosystem, are vital for healthy functioning, and everytime a species declines in abundance or is lost, the system as a whole becomes more fragile to disturbances such as diseases, extreme weather events – less able to bounce back and adapt.

“All species, including humans, are embedded in a complex network of interactions. If something happens to one, it could have cascading impacts on the others” – Daren Evans, ecology and conservation scientist

The relationships between species in an ecosystem’s food web have a big impact on ecosystem function. Changes in the presence and number of predators or herbivores in the system can create a domino effect of impact throughout the entire system. This phenomenon, called a ‘trophic cascade’ happened when wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park, after decades of predator control reduced their numbers. The wolves controlled the ballooning Elk numbers, which allowed trees a chance to grow and stabilize river banks. The abundance of trees brought back countless species of birds and beavers to the rivers, reducing bank erosion and altering the course of rivers.

Ecologist, Dr Daren Evans uses the game of JENGA as a metaphor for the interdependent nature of ecosystems, and the importance of species diversity to resilience:

“As the game (Jenga) progresses, the tower becomes less and less stable as more bricks are removed – a poignant demonstration of the current state of nature. Although plants and animals are still present, the loss of species and their interaction with one another makes the ecosystem more and more fragile. And, as everyone knows, ultimately the whole thing will come crashing down”. – Daren Evans

The greater the diversity in species, the longer it takes for the system (or the game) to reach collapse. If you played Jenga with 27 blocks rather than 54 (i.e a smaller, less diverse ecosystem), you would expect the game to be over much faster. However, a recent study alarmingly concluded that entire ecosystems, previously thought to be relatively stable due to their size and capability to diffuse impacts across large areas, such as the Amazon rainforest, can collapse much faster than was originally assumed. In these instances, the enhanced connectivity and interdependence of these large ecosystems, allows a highly stressed system to unravel more quickly once a collapse starts.

Losing genetic diversity

Not only are we losing species diversity as species disappear from ecosystems and from the planet altogether, but as species’ populations fall, so too does their gene pool. Every animal and plant has a unique genetic code (their DNA), and every time they breed, this genetic code gets recombined and creates a new, different combination. Sometimes this new combination is beneficial for the animal/plant and gives them an advantage that they then pass on again to their offspring. This is what is known as natural selection, which ultimately enables species to evolve. If this gene pool shrinks (i.e the diversity of DNA combinations), then the options for recombination and adaptation also shrink. Sometimes there are so few options that individuals interbreed or they breed with close relatives with similar genetic codes. We all know that inbreeding in humans leads to poor health outcomes and sometimes infertility, and the same is true for animals and plants. In this way, shrinking animal and plant populations makes them more vulnerable and less able to adapt to changing conditions, which in the current rapidly shifting climate, is more important than ever.

Why does it matter if an ecosystem collapses (how does it affect me?)

When ecosystem function is compromised, so too are ecosystem services. The IPBES Report found that current negative trends in biodiversity and ecosystems will undermine progress towards 80% (35/44) of the assessed targets of the Sustainable Development Goals, related to poverty, hunger, health, water, cities, climate, oceans and land. Loss of biodiversity is therefore not only an environmental issue, but also a developmental, economic, security, social and moral issue as well.

“Biodiversity…holds critical genetic information, which could help us cure diseases, create new drugs, design climate-resilient crops and more. Every time we lose one of these species, we also lose some of that crucial information.” – Lee Hannah, senior climate change scientist at Conservation International

The ultimate example: The COVID-19 Pandemic

There is a link between dwindling biodiversity and human intrusion into wild places, and the rise in infectious pathogens. Greater clearing of habitat and biodiversity loss leads to greater interactions between humans, wild animals and livestock animals which are stocked in high densities. This creates the perfect storm for zoonotic (animal-borne) pathogens to jump the species barrier and infect humans.

One study suggests that agricultural drivers were associated with over 50% of zoonotic infectious diseases including swine flu, Nipah virus, MERS, bovine tuberculosis, rabies, West Nile virus, SARS, COVID-19 and Ebola. It concluded that one proactive solution to preventing zoonotic disease emergence is to conserve biodiversity.

Is biodiversity declining or just changing?

You might be asking, won’t new species/plants/animals take the place of the ones dying out?

They might. Nature is resilient and species are constantly adapting, and some ecosystems undergo what is known as a ‘regime shift’ before they completely deteriorate. Rainforests might turn to grasslands, and grasslands might turn to savannahs – there is still life, but there is less diversity. In this instance, highly adaptable ‘generalist’ species might replace the space that once supported multiple ‘specialist’ species. For example, Australia is rapidly losing hollow-dependent mammals such as gliders and small marsupials due to tree-clearing. The brushtail possum however, is doing really well, because it can adapt to a variety of food sources and has made use of urban spaces as habitat.

Our current rate of biodiversity loss means we are almost certainly losing species faster than we are naming them. We are effectively burning a library without knowing the names or the contents of the books we are losing. - Tanya Latty & Timothy Lee

Haven’t there been extinctions before?

Yes, but the current rate of extinction is at least tens of hundreds of times higher than it has averaged over the past 10 million years.

From what we know of the fossil record, life on Earth has undergone five mass extinctions, where the loss of species rapidly outpaces the formation of new species. A mass extinction is usually defined as a loss of about three quarters of all species in existence across the entire Earth over a ‘short’ geological period of time.

The evidence is compelling that we are in the midst of a sixth mass extinction event. Whilst the IPBES report estimates that ‘only’ one quarter of all species are threatened with extinction, it is occurring over a drastically short time period of several centuries, compared to the fifty thousand to 2.7 million-year duration of the past five mass extinction events. If species were declining at the background extinction rate (the random loss of species over time, determined from the fossil record), the number of species lost in the last century would have taken between 800 and 10,000 years to disappear.

Indeed, some academics argue that this current sixth extinction event actually began 2 million years ago, when our Hominid ancestors first began to use the large-carnivore niche in Africa. Wherever humans have gone since then, the disappearance and extinction of species has followed.

“It would likely take several millions of years of normal evolutionary diversification to “restore” the Earth’s species to what they were prior to human beings rapidly changing the planet” – Frédérik Saltré and Corey J. A. Bradshaw